Cloth is either made from plant material (cottons, flax) or animal materials (wool, silk, leather). When dying these materials you need mordants – additives that help the colour grab on to the material and set it in place. It’s a complex art and experts are known as Master Dyers for good reason. The colour you get depends on pH and the type of mordant used. Common mordants are alum, iron sulphate, copper sulphate, tin chloride and tannic acid. A dye may be brown with one mordant but green when used with a different mordant, and the type of fabric used also effects the colour. There’s a lot of information out there about using natural dyes on both wood and textiles but getting the colours right on metal lacquer is rather different.

Natural dyes are usually used in water and can react very differently in an alcohol and shellac mixture. Some simply won’t work (onion skins for instance) and others colour the solvent incompletely, or float to the surface of the lacquer and wash off (wood dyes are particularly bad for this, even those that are sold as alcohol soluble). Bismarck brown, a common Victorian stain, produces a brown/red colour when used as a wood stain but is scarlet when used in lacquer. It doesn’t adhere well either…

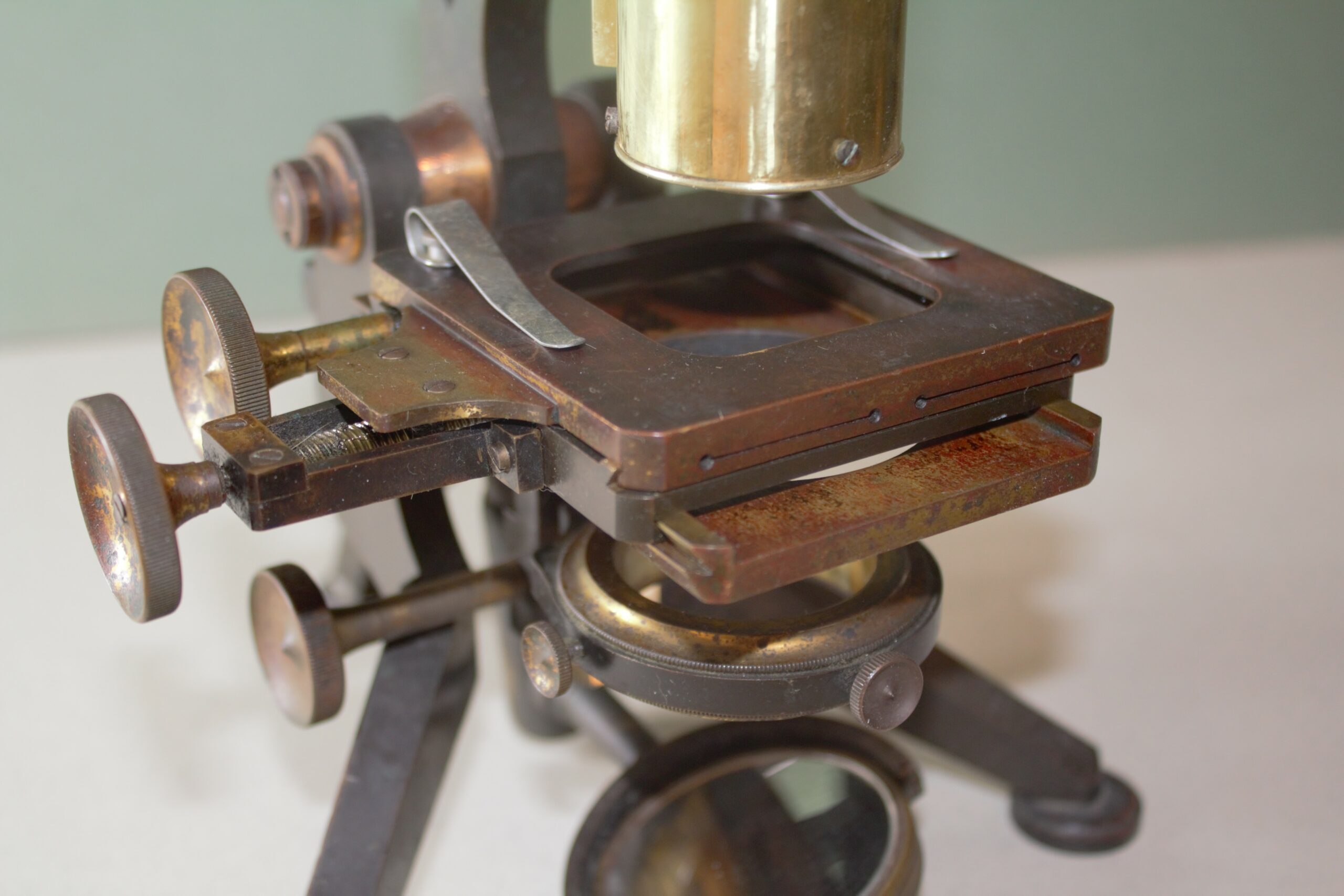

Brass contains copper and zinc but when you restore an old microscope you never know quite how much of each you are dealing with. Even though you are not really dying the metal, your lacquer sits on top of the metal, the zinc and copper content of the brass can still alter the colour of the lacquer. It can be tricky to know what will happen. You might apply a lacquer that appears to be a rich gold on a test piece of brass, but when applied to the antique microscope it comes out a dull yellow. It’s a pain. I have one lacquer which when it first goes on has a slight green tinge to it (possibly a reaction with copper) but after a week or so the green tinge dissipates and it turns yellow again. I haven’t quite figured this out but I think the green copper complex is unstable. It degrades in daylight. It only happens on old brass, not new brass – just to add another layer of mystery.

Why bother, you ask? Why not buy a can of spray on nitrocellulose lacquer?

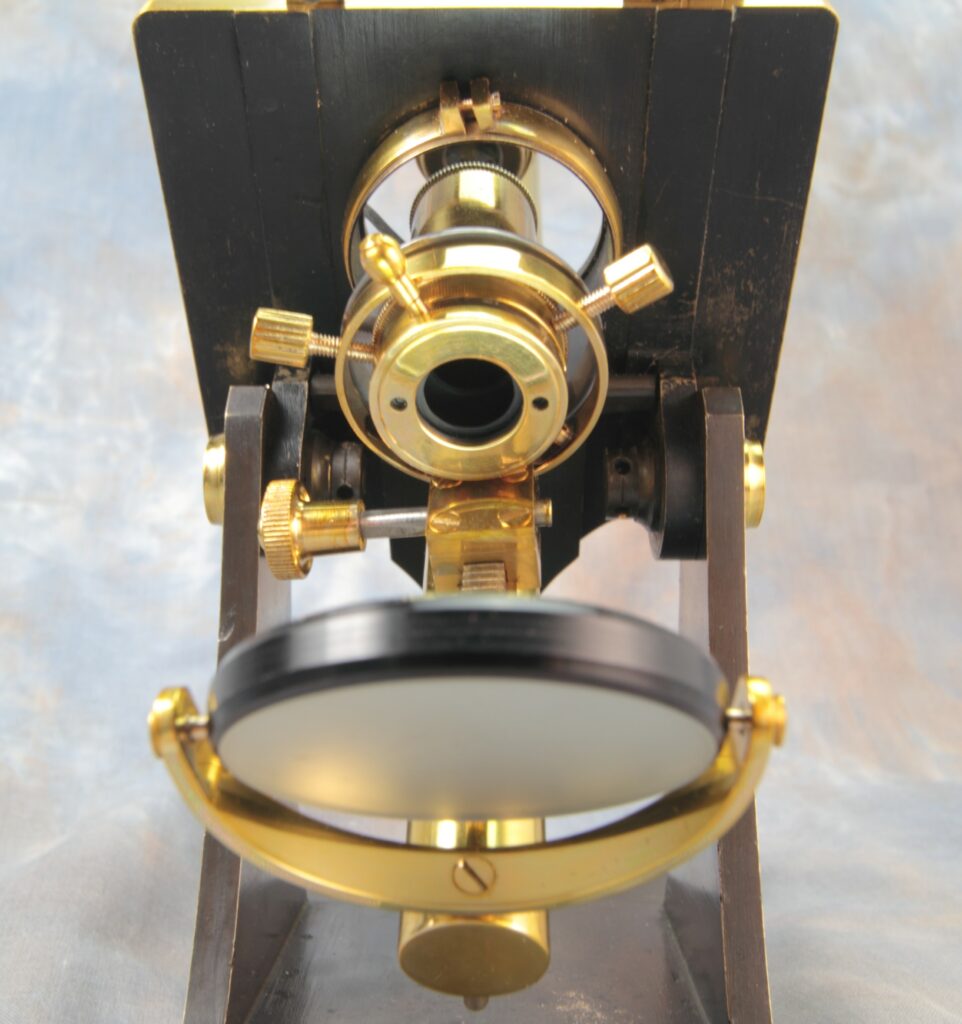

Why? because I like things to be done properly and I don’t want every microscope I restore to look exactly the same as the previous one. Different makers used different colours. Different lacquer batches from the same maker were different colours. Lacquer colours changed with fashion. Some early Watson microscopes used a deep orange gold lacquer, later ones were very pale. There was a lot of variation and considerable beauty. I like to restore things using the same ingredients as were used originally. If you don’t do that then you are not restoring anything, you are doing a bodge job. You wouldn’t use acrylic paint on the Mona Lisa would you? (God forbid she ever gets damaged). You might use a brush with a plastic handle, or maybe artificial bristles (if you can make the same brush strokes) but you wouldn’t use modern paints. Besides, it’s fun. Research is fun and experimentation is fun.

‘No synthetic dye has the lustre, that under-glow of rich colour, that delicious aromatic smell, that soft light and shadow that gives so much pleasure to the eye. These colours are alive.’ Violetta Thurston

As I have already said, not all dyes are created equal. Some are particularly wonderful. Dyes such as turmeric are known as substantive dyes, they don’t need mordants to adhere to fabric and they are not too temperamental in lacquer. In fact they are very, very reliable. Turmeric is the basis for almost every lacquer I make and it never fails to be yellow. Obviously, being a natural product there is some variation in the intensity of the yellow but it is always, without fail, yellow.

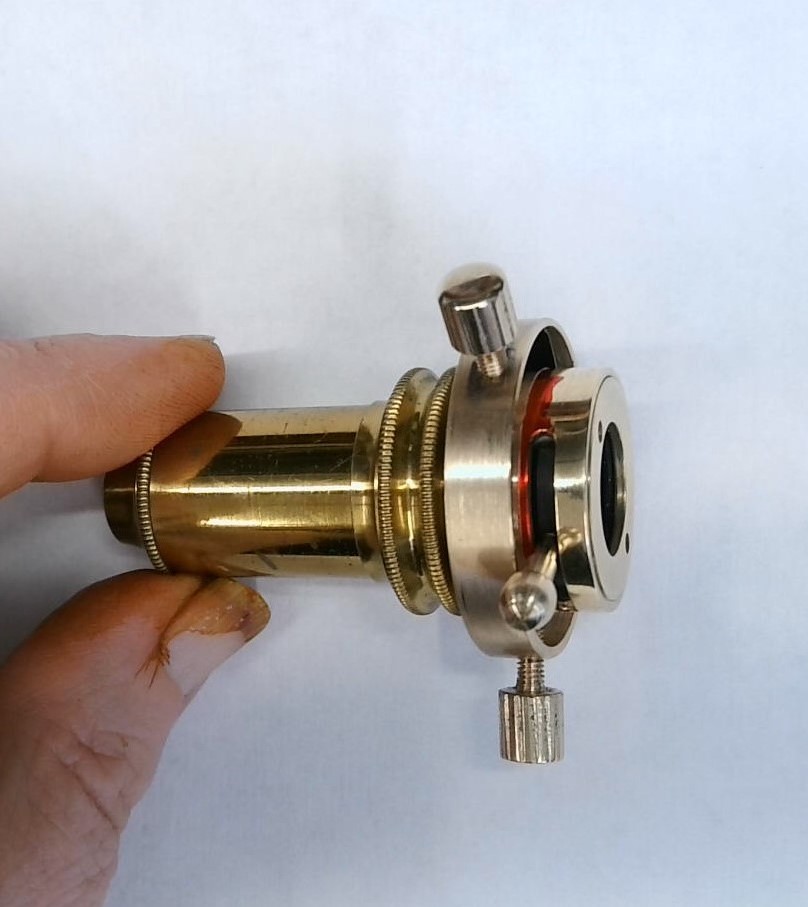

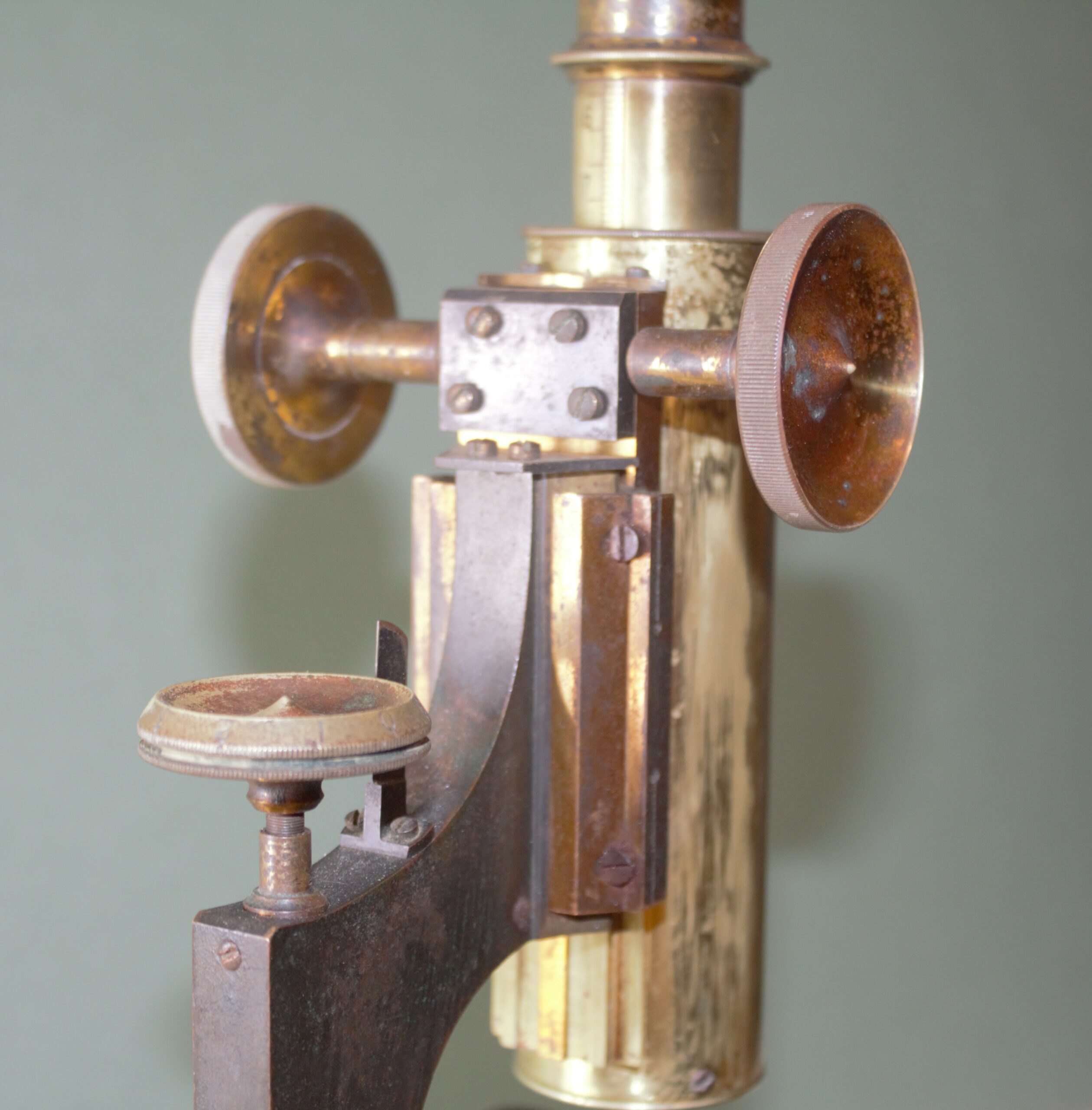

Today I had a small breakthrough, I have a tiny piece of a microscope which I repaired for a customer. The piece is repaired but the repair damaged the lacquer so I have to colour match and re-lacquer. This lacquer is a smoky gold colour. Warm gold with a tiny hint of brown. I have tried all sorts of ways to get browns and whilst I have had some success, I have not yet found a reliable source of brown which I can mix with other dyes. There are modern dyes, but I want to stick with products which were commonly used in the Victorian era.

I was browsing textile dying websites for inspiration when I stumbled across black walnut hulls. Walnut! Of course! They used to make ink for pens from walnut hulls. It was a VERY common ingredient in the Victorian era. I would be amazed if they didn’t use it. I have some water based walnut hull ink in the cupboard and it is a lovely nutty brown. A little research and I discovered that walnut is also a substantive dye that is brown in both alcohol and water. I’m waiting for walnut hulls to arrive from eBay. I am very keen to test it out. I don’t know why I didn’t think of it before!